|

© 2000 Rogue Written with kindly inspiration from Ken Cougar It was a very long time ago, in the days before the rain forest when the great stone cities were teeming with people, that a piece of the sun fell from the sky into the ocean and gave birth to the giant god T'unu-kan. Some fishermen on the shore were the only ones to witness the miraculous birth, but only one of them would live to tell others of how it happened, and by the events of that day his life and the lives of all of his people would be changed forever. Uaxac the Fisherman was the first to see the glowing ball detach itself from the sun and fall slowly through the sky. "Look!" he said to the others around him. "The Sun God is crying. What could have saddened him so?" Nobody could guess. They had been good people and had prayed faithfully to the many gods whose powers controlled the world. They had made offerings and sung loving songs, so why would the Sun God weep? All of the fishermen ran to the water's edge and watched in awe as the brilliant orb fell lower and lower and finally vanished on the horizon. There was a bright flash, like lightning, and then nothing more. "It was just one single tear," one man said. "The Sun God must not be too upset." The others agreed and went back to repairing their nets. Only Uaxac remained behind, staring with concern out to sea at the spot where the piece of the sun had disappeared. "Great Sun God," he whispered. "I apologize if we have made you sad. If you will tell me what we have done, I promise you that we will try to make you happy again." That little prayer must have earned Uaxac the Sun God's blessing, which is why he alone was spared. Uaxac would realize later that it was not a tear that he had spotted, but the Child of the Sun himself, the god T'unu-kan, coming to the sea to be born. Never could he have imagined the terrible birth-agonies that the sea was experiencing, but they would soon become all too clear to him as he stood gazing at the horizon. At first it appeared that the water was rising into the sky. Uaxac thought this to be very strange, and continued to stare as the sea grew higher and higher. "Brothers," he called nervously. "Come here. The sea is turning into a mountain." "Come and help us here," was the only reply. "We have work to do." Uaxac was afraid now. The mountain in the sea was growing larger before his eyes. Only when white froth crested along its peak did he realize that it was not a mountain, but a monstrous wave the likes of which no one had ever before seen, and it was almost on top of him. "Brothers!" he cried. "Run away!" but it was too late. No sooner were the words past his lips than the wave was upon him. His ears filled with a roar like a hundred jaguars. Dark water and raging foam surged violently around him. His body was battered about, flung skyward for an instant, then plunged deep and spun round and round. He felt certain that he was going to die, but suddenly there was soft sand beneath him, and he was left lying upon it as the water retreated back into the sea. It was a long time before he was able to get up; when he did, he could not tell where he was. The other fishermen were gone; so were the boats and the nets and the huts that they had built upon the shore. The water still leaped and raged, and fearing that it would rise up again, Uaxac scrambled up the beach and onto the hill that overlooked it. Weakly he called to his brothers but there was no answer. The sea had devoured them all and had left nothing behind. Nothing, that is, except for Uaxac, who sat alone on the hill then and lamented their loss. Then he saw another strange sight. The sea was still writhing and lurching for as far as he could see, but out on the horizon a black shape was silhouetted against the sky. It could not be a wave, for it was round and bobbed in place, more like a huge ball. Uaxac watched it for a long time and realized that it was floating toward the shore. Eventually it was close enough that Uaxac could tell that it was not a ball, but the head of some gigantic animal. It looked very much like that of a black mink, but much, much bigger than any that had ever before been seen. It seemed to grow even larger as it floated toward him, and much to Uaxac's surprise he saw its eyes blinking in the spray. The head was alive! Incredibly, it began to rise into the air. Beneath it there was a stout neck. To either side of it the water was churned into white breakers, and then huge shoulders surfaced, the waves crashing against them in great frothing sprays. Uaxac rubbed his eyes in disbelief, and watched dumbfounded as a great black chest emerged from the water, followed by a long, lean torso, and then two strong legs that crashed heavily through the sea as they carried the creature toward land. Its size was staggering -- already it towered higher than the biggest tree Uaxac had ever seen, and still it kept rising from the water. One giant foot burst up from the depths and swept forward through the air, trailing a great sheet of water behind it. It came down on the shore with a loud boom and sank deep into the sand. The creature hesitated, its immense body swaying slowly, and then suddenly it toppled forward. Uaxac was thrown into the air from the impact, the noise of which stabbed painfully at his ears. He fell hard and rolled down the hill onto the beach, but he was not hurt, and hastily he scrambled back to his feet. The sea was still in turmoil, its waves thrashing loudly against the legs of the creature that now lay motionless on the beach. Uaxac was terrified, but as much as he was frightened he was also curious, and could not resist creeping forward like a mouse to investigate. To say that nothing like it had never before been seen is saying too little. Uaxac could honestly not tell if it was an animal or if it was a man. Its enormous body was covered all over in dense black fur, which while wet made the creature look like it was carved out of onyx. Uaxac crept slowly around it, though he was not brave enough to try to touch it. Except for the head, the body under the fur seemed to be shaped just like a man's. He looked very closely at its hands to be sure. Only men have hands, and this creature did, too, even though they ended in big claws instead of nails.

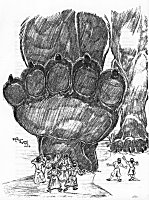

He made his way close to its head, which was as much like a mink as the rest of it was like a man. Warm breath blew past him from an open mouth that was filled with teeth as big as Uaxac was. Water still trickled from the thick coat of fur and made puddles around the creature, puddles in which the sun's reflection danced. The sight of that reflection brought understanding all at once to Uaxac. Of course -- the sun! That ball of fire that he had seen had not been a tear after all. It had been the holy seed of the Sun God himself, and where it had fallen into the fertile sea this offspring of fire and water had been birthed. Uaxac stumbled backward, overwhelmed by the revelation, and fell upon his knees. He trembled in the presence of the newly born god and sputtered hasty and earnest prayers. There was no answer, however, only the warm breeze of the god's breath rushing past him, and the equally warm touch of the Sun God's gaze upon his back. At last Uaxac felt the courage to raise his head and peer at the god's vast face. "When you wake," he whispered, "my people will welcome you. I shall go and tell them of your glorious birth!" With that he jumped up and began to run for home. It was a long journey from the shore to the city. Uaxac ran as fast as he could, slowing down to catch his breath only when he was nearly exhausted. He was far too excited about the arrival of the new god to waste time, and thus he presented a terrible sight to the priests when he stumbled into their chamber well after the sun had set. "He's here!" he croaked, falling down and crawling toward the astonished priests who had just gathered for their evening meal. "I saw him! He is the Child of the Sun!" "What is all this?" one priest cried, leaping to his feet in alarm. "Who is this man?" Uaxac was panting and waving his arms. "The god! He is a giant! All black, an animal, a man, I do not know! He came from the sea! That is, he came from the sun!" "Slow down," another priest said. "Who are you talking about?" "The god!" Uaxac shouted. "He came from the sea!" "But you said he came from the sun." Uaxac waved his arms more wildly. "He did! He came from the sun and then he came from the sea! I saw him! He is as big as a mountain!" "Look at this." One of the priests pointed to a big lump on Uaxac's forehead that was starting to turn dark purple. "The poor man has hit his head. No wonder he is acting so crazy." "But I am not crazy," Uaxac protested. "I saw the god come from the sea. We must be ready to welcome him!" "There, there," another priest said as he gently held onto Uaxac's arms. "We will prepare a bed for you. You can tell us all about this god from the sea tomorrow." "And the one from the sun," the first priest added with a little smile. Uaxac's eyes darted from one man to the next. All of them were smiling at him as though he were a silly child. "But...but it is true," he said weakly. "Of course. We understand. We promise that we will greet the new god tomorrow." Then they gave him a cloth to wrap around his head and some isava balm for the lump, and told him to go home. Miserable, Uaxac shuffled out of the temple and wandered through the streets. "Why do they not believe me?" he lamented. "Surely the Sun God speaks to them more than to a poor fisherman. Surely he would have told them to expect the arrival of his child." It made no sense, and the more that Uaxac thought about it the more confused he became and the more it made his head hurt. At last he stretched himself out by the side of the road -- he could not go home, of course, for his home had been swallowed by the sea -- and fell into a fitful sleep. In his dreams the breath of the new god warmed him against the evening's chill. Staring long into the shining black, vast expanse of fur that seemed to reach as deep as the ocean, Uaxac heard the god's name whispered to him by a sonorous voice: T'unu-kan. He was sore and stiff in the morning when the sunlight woke him up. With a groan he climbed to his feet and, eager to see how the priests had prepared the welcome, he ran as fast as he was able back to the temple. To his dismay the great courtyard was empty, save for a single bird who picked at the grass blades that poked up between the cobbles, and who flapped away noisily when Uaxac ran past. "Fathers!" he shouted. "Why have you have not prepared?" "Be quiet, You!" It was one of the young acolytes who assisted the priests in their ceremonies. "The Fathers are at prayer." "But T'unu-kan must be made welcome!" "T'unu-kan? Who is that?" Then the boy sneered. "Oh, it is you! You are the crazy man who interrupted the Fathers in their evening meal." "I am not crazy!" Uaxac growled at the boy. "I saw him. T'unu-kan must be made welcome, or he will be insulted." One of the priests emerged from the depths of the temple. "What is going on? Oh..." He smiled widely at Uaxac. "Hello again. How is your head this morning?" Uaxac was beside himself. "Father, please believe me!" he cried, almost in tears. "I saw him with my own eyes. He is T'unu-kan, and he is the child of the Sun God. He was born in the sea. Please, please, let me take you to him. Then you will believe me!" The priest looked at him pityingly and tugged at his chin. He was quiet for a very long time, and then he turned to the boy. "Go and gather them all," he said softly. "This man will not be at peace until we have seen this Child of the Sun for ourselves." Uaxac fell to his knees. "Thank you, Father!" he sobbed. "Please, let us hurry." "Of course." It was with no small amount of grumbling that the priests began to gather before the temple. "Must we travel all the way to the ocean?" one complained. "It will take all morning." "And the roads are difficult." "All because a fisherman thought the saw a god!" Uaxac was insistent, however, and the priests reluctantly followed him down the pitted and dusty road. He fumed impatiently as they dragged their heels and complained and balked at crossing the muddy areas. Many were the times the priests wanted to turn around and go home, but Uaxac desperately urged them on. They dawdled and moaned so much that the sun was already very high by the time they reached the spot where Uaxac's fellow fishermen had disappeared. There was no sign of the god. The priests glared at Uaxac, who ran down the hill onto the sand and stammered, "But he was here. I saw him!" "Of course you did," said one of the priests. The tone of his voice was very cold. Uaxac tried to protest, but the priests turned their backs on him and started back toward the city. "Not another word out of you," one called over his shoulder. "You have wasted enough of our time. If you speak of this so-called god again, you will be punished." They grumbled and complained loudly and cast angry glances back at poor Uaxac, who wanted very much to make them believe, but nonetheless feared the punishment that they would mete out if he angered them. He ran along the shore in both directions, trying to find some sign of the giant god that had visited him the previous day, but the tide had washed the beach clean. Finally Uaxac gave up, and with a heavy heart he started along the path back to the city, following the priests but staying far behind them out of shame. Some time later, with the sun beginning to sink lower in the sky, Uaxac reached the foot of a high hill. It was part of a ridge that was the last obstacle to climb before he reached the city, which lay nestled in a valley on the other side. He started to trudge along the steep path, but was surprised to see the priests clustered ahead, just at the crest of the hill. Too ashamed to face them, he stopped and waited for them to continue onward. Strangely, though, they stayed where they were. They were talking excitedly among themselves and pointing into the distance toward something that Uaxac could not see. Suddenly his heart began to race. He broke into a run. At the far end of the valley stood the god, bigger than a mountain, blacker than a shadow. Uaxac could see him clearly as he crested the hill and stood among the astonished priests. The god stood among trees that were known to be among the largest in the world, and yet they reached only just past his knees. Sunlight gleamed off of an amulet about his neck that was his only adornment. He stood with his hands on his hips, his muzzle upraised toward the sky. Uaxac pointed excitedly. "You see!" he shouted. "There he is. It is T'unu-kan! We must welcome him!" "Be quiet!" the priests barked at him. "We know what to do." That did not seem to be so, since they were only standing and staring and whispering to one another. Uaxac tugged at their hands. "Come on, then! We have little time to prepare." Angrily the priests pushed him away. "We will prepare," they growled. "You will stay here." "But I ..." "What does a fisherman know of the gods?" one of the priests sneered. "It is best to leave such matters to us." "But..." "Stay here! The Child of the Sun does not need a dirty fisherman defiling his welcoming ceremony." They whispered excitedly to one another some more, and then started down the hill. One of them shoved Uaxac very roughly when he tried to follow, and the angry look that Uaxac was given told him that the priests meant what they said. Despairingly he watched them run down the hill toward the city, where many people had begun to gather in the temple courtyard, and then he turned to gaze upon T'unu-kan. The god was still peering at the sky. He turned his head this way and that, as if searching, and then slowly turned his whole body about. A cloud of dust rose from below him, and Uaxac could see tall trees shuddering and falling around his feet. Meanwhile, the city below was abuzz with activity. People were rushing about, gathering offerings of fruit and cattle. The god, however, had not yet taken any notice. He was more interested in the trees, and was crouching now and peering closely at them. With one hand he uprooted one and raised it to his muzzle. Even at this great distance Uaxac could see the god's huge nose quivering as he sniffed at the leaves. Then the god opened his mouth wide and bit off the entire crown of the tree, leaving only the bare trunk, which he casually tossed aside. The priests hurriedly finished their preparations. Flowers were strewn about the courtyard, and all of the priests knelt in a group, surrounded by their acolytes. Minstrels played cheerful music with flutes and strings, the strains of which tickled Uaxac's ears up on the hilltop. It did nothing to ease his disappointment, however. It was unfair that the priests would not allow him to take part in the ceremony. Had it not been he who had witnessed the god's arrival? Had it not been he who had basked in the warm celestial breath before any other man? Then again, he was still just a lowly fisherman. The gods, as the priests had always reminded everyone, had no interest in common people and in fact found their presence to be distasteful. That was why the streets were beginning to empty; the entire population of the city had been banished to their homes, forbidden to come out until the god had spoken with the priests and given them his blessings. At least I can still watch from up here, Uaxac thought. T'unu-kan, however, did not approach. He remained squatting on his heels at the far end of the valley, which seemed a far more interesting place for him at that moment than the ceremony being held in his honor. Uaxac watched him closely, transfixed by the sight. T'unu-kan was handsome with the sunlight glistening off of his ebony hide, his whole body looking as though the shadows of the mountains had sprung to life and come together in one gigantic and magnificent form. It seemed strange that the Child of the Sun would be so utterly black, but then again, Uaxac reminded himself, T'unu-kan was still young. No doubt he would develop a fierier hide as he matured. The priests were become restless, fidgeting, some of them standing and craning their necks to see if the god was approaching. T'unu-kan still paid not attention. He reached down through the trees and plucked something small and wiggly from among them. Uaxac squinted, but could not tell if it was a jaguar or a bear before the god ate it. For a brief moment it occurred to him that it might have been a man, but that idea was preposterous and he put it out of his mind. At last the god stood up. He dusted off his hands on his furry legs and then raised his arms skyward in a gigantic stretch. He yawned, revealing long white fangs behind his lips. Finally then he began to walk toward the city. Each huge step covered more distance than Uaxac could throw his fishing net. Each heavy footfall pushed down stout trees as though they were merely blades of sawgrass. The god's massive legs pushed aside branches with ease and sent the birds squawking into the air in great colorful plumes. As the giant drew nearer, Uaxac could feel the earth tremble and a pounding like distant thunder started to echo off the hillsides. The priests hastily returned to their positions in the center of the courtyard. The musicians played louder. Their faces were tense and eager. T'unu-kan reached the wall of the city and stepped over it as easily as stepping over a log. As the earth quivered from the impact, the high priest raised his arms in prayer. The sun's rays gleamed off of his jeweled headpiece; as if in response, a beam of sunlight glinted off of the necklace that bounced against T'unu-kan's broad chest. Uaxac watched breathlessly. The great god took another step. His enormous foot swept through the air and descended, crashing down hard onto one of the many houses that lay between him and the temple. For a split second Uaxac saw a pair of figures crouched in the doorway and peering out in bewilderment, just before the god's clawed toes settled upon them. The sight sent a terrible jolt through Uaxac. "What is happening?" he said out loud. "T'unu-kan, be careful!" The house and everything in it was pressed flat beneath the god's foot. Without even a downward glance T'unu-kan took another step, his leg rushing forward through the air. The top of his toes swept against a pair of houses and smashed them to pieces, sending bits of stone and wood hurtling in all directions. Uaxac's mouth fell open at the sight. "T'unu-kan!" he shouted. "Why are you doing this?" The god did not pause for even an instant. His foot came down on another house, and it too was smashed to bits beneath his sole. Uaxac raised his eyes pleadingly to the god's face, and was dismayed to see the great brown eyes fixed somewhere off on the distant horizon. One of the colorful forest birds swept in front of the god's nose, and T'unu-kan slowly turned his head, following the bird with an interested gaze. While watching the bird he took another step, and Uaxac realized what was happening. The god was so enormous that he did not even notice what was below him. His eyes were thoughtful and curious. They held no malice, no hint of awareness of the houses or the people he was crushing beneath his feet... ...or of the priests who had gathered directly in the giant's path. "Oh, no..." Uaxac croaked, his eyes growing wide. "T'unu-kan, please look down. Please!" His plea went unanswered, though. Uaxac watched helplessly as the god's mighty foot swung forward, its shadow surrounding the priests, whose heads were bowed reverently, unaware that the god had not seen them. "T'unu-kan!" he wailed in desperation. "Look down!"

Things seemed to happen very slowly then. There was no sound, the silence unearthly. The god's foot descended. His heel landed noiselessly in front of the priests and sank down into the earth, pushing up a rim of soil around it. The muscles of his gigantic leg shook with the impact, the sun's rays breaking into dancing rainbows over the dark fur. The massive foot seemed to pause, hanging motionless in the air. The priests slowly raised their heads and stared for a long time at the vast black sole that loomed over them. Even more slowly they began to raise their arms over their heads. Then all at once the immense foot slammed down with a jarring crash that shattered the silence. The priests instantly disappeared beneath it. The ground rippled, sending the acolytes sprawling helplessly. T'unu-kan moved forward, and as his ankle flexed a terrible redness bubbled up around his toes. His foot rose again, leaving what was left of the priests stamped deep into the earth behind him. Adding to the horror of the priest's demise was Uaxac's sudden realization that the god was heading straight for him. The courtyard had seemed so far away, but with just one more stride the god's foot crashed to the ground right at the base of the hill. Uaxac stood frozen with fear as the other leg rose skyward. The great foot rushed past his head, and for an instant Uaxac could see red smears upon its underside. The foot continued forward, sailing through the air and coming down hard on the opposite side of the hill; the other followed it a second later, the wind whistling past the clawed toes as they swept into the distance. Uaxac was left staring at T'unu-kan's back, and at the enormous tail weaving like a giant, furred anaconda through the air behind the god's rump. The shaking subsided as the god wandered off, pausing in the distance to examine a curious outcropping of rock that capped a nearby hilltop. He never once looked back, nor did he even bother to scrape the pitiful remains from the bottom of his foot. Thin cries of despair reached Uaxac's ears. He turned to see people stumbling from their homes into the streets. Some had gathered around the flattened houses and were gawking at them in confusion. Others were clustered around the huge footprint in the courtyard, and what was left of those who had fallen beneath the god's tread. The surviving acolytes were gibbering and gesturing wildly in the direction that T'unu-kan had gone. Uaxac felt sick. He had never before seen men die so horribly, stepped on like meager insects, and the wailing of those who were clawing through the rubble in search of their friends wrenched at his heart. He wanted more than anything to run away from the horrific sight, but before he knew it he found himself running down the hill toward the courtyard. He did not even know why. Something deep inside told him that he needed to talk to the people and make them understand what a terrible mistake the god had made. T'unu-kan meant no harm; he had simply been careless. Uaxac forced his legs to go faster, hoping to reach the courtyard before the acolytes began to say things that would frighten the people. It was too late, though. Already the youngsters had recovered their wits and were pointing angrily at the huge footprint. "It is no god!" one was yelling. "It is a monster sent to destroy us all. The gods are angry with us and we are being punished!" "No!" Everyone fell silent and turned to stare at the fisherman who had stumbled into the courtyard. "He did not mean it," Uaxac panted. "I watched what happened. He did not know that we were trying to welcome him. There must have been something wrong with the ceremony." "Be quiet!" the oldest one barked. "What do you know?" "I know what I saw! The gods are not angry with us, and T'unu-kan is not a monster. He is young and lost, and he is just so big that he never noticed us. All he wanted to do was go to the mountains; we were just in his way. If the priests had known how to speak to him they would have..." "Heresy!" All of the surviving acolytes had gathered together now and were glowering furiously at Uaxac. "How dare you preach to us what the gods are thinking?" Uaxac bit his lip and tried to think of an answer, and then his shoulders slumped and his arms fell weakly to his sides. "I don't understand it," he whispered. "I just know somehow." The oldest boy snorted and waved his hand dismissingly. Turning to the stunned and frightened people who had gathered around, he threw out his chest and called out in what he must have thought was a very authoritative voice, "We must mourn our fallen Fathers later. Right now, we must learn what it is that we have done to have offended the gods and earned from them this terrible curse." "It is not a curse!" Uaxac cried. "T'unu-kan means us no harm!" Someone suddenly stepped forward and pushed him roughly. It was the young acolyte that had scolded him when he went to the temple that morning. "Do not listen to him," the boy snarled. "He is crazy. Take him away from here before his stink offends the gods any further." "But..." That was as much protest as he was allowed before two burly men seized him by the arms. They were not gentle as they dragged him from the courtyard. Uaxac tried to plead with them, but one of them struck him cruelly in the cheek with his fist. "Shut up!" the man growled. "The last thing we need now is crazy fishermen making noise when we are trying to think of what to do." Uaxac opened his mouth but the man raised his hand threateningly, and Uaxac quickly closed it again. He hung his head and stayed silent while he was escorted to edge of the city, to the bottom of the same hill from which he had watched the god's unwitting rampage. Sneering, they threw him into the deep footprint that T'unu-kan had left there. "There," they said scornfully. "Now you can commune with your god." They turned and strode away quickly, leaving poor Uaxac alone. Back in the courtyard the young acolytes were barking stern orders to men twice their age and wisdom. The oldest one had even taken one of the blood-soaked robes from the print and placed it around his shoulders. If only I could make them understand, Uaxac said sadly to himself. He knew that it was no use, though, and he knew also that if he were to try to return to the city the young men would probably order him to be killed. With a heavy heart he climbed from the footprint and trudged up the hill to its crest. There he peered into the distance. T'unu-kan was nowhere in site, hidden no doubt behind the distant mountains, but he had left behind a trail of broken trees pressed down flat beneath his tread. Uaxac followed the trail with his eyes until it vanished into the distant haze. He felt a stirring in his spirit. "If they will not worship you," he said aloud, "then at least this humble fisherman will." Sharing his shoulders, he took a deep breath and marched determinedly down the other side of the hill, following the great trail of footprints toward the horizon. Gods move much faster than men do, however, as Uaxac soon discovered. He had imagined that the giant's trail would be easy to follow, but even though there was no rainforest in those days, the woods were still thick enough to make his progress agonizingly slow. For the rest of the afternoon he beat a path from one big footprint to the next, fighting through thickets and pushing his way through stubborn branches. Sometimes the vegetation was so thick that he could not see where the next print lay, but the fallen trees themselves told him which way to go; snapped off at their bases, they had been pressed to the ground all at once by the god's footfalls and lay in orderly rows that pointed the direction that T'unu-kan had taken. Every time Uaxac stumbled into one of these newly stamped clearings he would drop to his knees and feel for warmth in the packed soil. Every time, though, he was disappointed. Each footprint seemed to be even colder than the last. Time passed. The sun was setting now, and Uaxac was beginning to despair. The trees and the underbrush were growing thicker still, and before long he had lost his way. He tried to retrace his steps back to the last footprint he had crossed but he could not find it. The sun was hidden behind the leaves now, robbing him of all sense of direction. He tried not to panic, but the woods were growing darker. At last, with the light nearly gone, he caught sight of some fallen trees in the distance and stumbled toward them. To his relief he found another footprint, the trees all fallen in the same direction, pushed down from by a tremendous force from above. Five deep, round pits showed where the great toes had pressed into the soil. It was not much, but at least it was a more secure place than the depths of the woods to spend the night. Exhausted, Uaxac sat down on one of the fallen trees and buried his head in his hands. "What am I doing?" he moaned. "The god is miles away. How foolish to believe that I could have caught up with him." The sunlight was almost gone now. Uaxac heard something rustling in the underbrush and began to feel very afraid. He was alone in the woods and vulnerable, far from friends or shelter and very close to jaguars and other hungry beasts. Worried, he began to hunt about for whatever fuel he could find for a fire. Fortunately for Uaxac, T'unu-kan's earth-shaking footsteps had shaken enough dead branches loose that Uaxac was able to gather enough for a fire before darkness fell completely. With the last of the sunlight fading, he managed to gather enough wood to start a fire in one of the pits made by the god's toes; as the flames crackled to life, Uaxac used their glow to search for more fuel, until he had a comfortably large bonfire burning that was certain to frighten away the most fearsome predator. Feeling a little safer now, he huddled by the fire and peered glumly into the surrounding blackness. The terrible events that he had witnessed earlier that day played over in his mind, and particularly the priest's horrible death. "If only they had listened to me and prepared a proper welcome," he said bitterly. Then again, what had gone wrong with their ceremony? If anyone, the priests should have known what to do. Their magic had always worked before. The rains always came and made the crops grow; the fish had schooled when they were supposed to. Obviously the priests knew what they were doing and had kept the gods happy. Why had their magic failed to terribly this time? The ground shook suddenly. Uaxac gasped in alarm and jumped to his feet. He stood very still, cocking his head to listen. He thought that perhaps his imagination was playing tricks on him, but then the earth rocked again beneath his feet. His alarm turned to elation. "It is him!" he said excitedly as peered into the ebon darkness of the nighttime sky. There was no moon, and with the fire casting its glare in his eyes he could not even see the stars. Uaxac clambered out of the pit to get a better view, backing into the center of the clearing and peering intently into the night. The ground shook again, even harder. He knew that the god was coming -- but from which direction? The rumbling boom that accompanied each quake echoed on all sides of him. As much as he strained his eyes, he could see nothing overhead but the black dome of the sky and the countless stars glittering against it. But then he noticed something odd. The stars had vanished from the sky, as though the surrounding darkness had swallowed up their light. For the briefest instant Uaxac had the impression of something large rushing downward, as though the starless sky had collapsed and was falling to the earth. Immediately there was a tremendous crash, just inches away from him. The fire was immediately snuffed out. The ground beneath Uaxac's feet gave a mighty heave; at the same time a gust of wind caught him and knocked him backwards. He fell against the stump of a tree and threw his arms around it, holding on tightly as another crash rocked the earth, and then another, and another and another, each one making the stump and lurch and buck in his embrace. All at once everything was quiet. The jarring impacts ceased and the earth settled down. Panting, Uaxac slowly relaxed his grip on the stump and rose to his feet. Without the fire he could see nothing. It made him feel exposed and helpless. Reaching a hand blindly outward he groped in the darkness and then took an uncertain step forward. "T'unu- kan?" he stammered. There was no answer. Uaxac closed his eyes tightly and opened them again after a few seconds, but still there was nothing, not even a sliver of light. Even the stars overhead were no longer visible. The air was heavy with a strange scent, not unpleasant, all heavy and musky like an animal hide. Uaxac's ears were filled with the sound of storm winds rushing through the trees, but despite the noise not a breeze stirred near him. Bewildered and frightened, Uaxac stretched both arms out ahead of him and began to pick his way blindly across the clearing, feeling his way among the flattened trees with his feet. Never before had he felt so lost or so vulnerable. "T'unu-kan?" he whispered. "Are you here?" Still there was no answer; there was only the unnerving roar of the wind that somehow blew nearby while the air around him did not stir. Uaxac stumbled on a branch that protruded from one of the fallen trees and fell to all fours with a startled yelp. He was desperate for someplace to hide and began to crawl forward, whimpering in terror. Abruptly his nose bumped up against something hard. Startled, he jerked his head back and reached forward with both hands. They fell upon a firm, smooth surface, much like polished stone. Uaxac was certain that there had been nothing like this in the clearing before. Baffled, he explored with his hands. The object, whatever it was, tapered smoothly downward toward him, drawing to a blunt point that nearly touched the ground between his knees. He leaned further forward, his hands sliding along the featureless surface as it widened. His stretched his arms as far as he could and felt short, thick strands of rope piled upon one another. "T'unu-kan?" The hard mass suddenly rose up from the ground, carrying Uaxac with it. He slipped off of its polished face and fell on his back with a grunt. A powerful gust of wind surged past him, and then the ground beneath him seemed to come alive, leaping and rolling and quaking much more violently than before, as though something was struggling beneath the soil to get out. The deafening roar of falling trees and the crack of splintering wood assailed his ears. Uaxac was convinced that the world was coming to an end. As the ground rocked beneath him he tucked himself up in a tight ball and covered his ears. The earth's motion rolled him about helplessly; the sound of crashing timbers rang in his ears no matter how hard he tried to block it out. The air itself shook as though it was being torn apart. As suddenly as it had begun the shaking ceased. The echoes lingered for a few seconds and then died away, leaving only the sound of the wind blowing through the trees, while still not a single breeze stirred around him. Uaxac sat motionless, afraid to move a muscle lest it somehow entice that ghostly wind stir the earth into frenzy again. The stars were once again visible. Aided by their gentle glow, Uaxac's eyes began to adjust to the darkness. Nervously he climbed to his feet and peered across at the sea of flattened timbers that lined the floor of the clearing. There was no trace of the mysterious polished stone that he had stumbled upon, just fallen trees and broken stumps. Baffled, he turned in a slow circle, peering deep into the gloom. There it was. Uaxac let out a sharp cry and staggered backward until he fell over one of the fallen trees. He sat staring for a long time, barely able to breathe. The faint starshine provided just enough light to allow him to see what he had blundered upon in the darkness. It was a toe. The smooth surface that he had encountered belonged to the great claw that jutted from its center. In the dim light Uaxac could see others like it resting on either side. As his eyes adjusted further, the rest of the god's foot came into view. It lay firmly on a bed of fallen trees. Above it a muscular leg rose into the air like an ebon pillar, visible only as a starless silhouette against the starry sky. Uaxac's eyes followed its outline into the sky, right up to its knee, above which the stares still shown. Terror and uncertainty gave way to exultation. Grinning, Uaxac began to clamber breathlessly over the smashed and scattered trees. He fell several times, but jumped to his feet right away and kept going. The god's titanic bulk stretched into the distance ahead of him. It seemed to go on forever. He pushed onward, his heart pounding excitedly against his ribs. A hand the size of a house appeared in his path. He scurried around it and scrambled onward, following the arm along its length, stumbling around the bulk of the shoulder, until at last he stood before the face of the god. T'unu-kan's head was turned to the side, his muzzle slightly parted, the tips of his great fangs gleaming in the starlight. Uaxac now realized that the mysterious wind that could be heard but not felt was actually the roar of the god's lungs. He smiled, closed his eyes and held his arms outstretched, letting the god's sweet breath waft past him. His hair whipped out in a billow behind his head, and then swept forward again as the god inhaled. The simple communion left Uaxac speechless, his heart fluttering joyfully. For a long time he just stood before the god's open mouth and basked in his blessing. Somewhere beneath the rush of air he could hear faint music, a simple melody of four notes repeating over and over, a celestial hymn that was carried in the god's breath itself. Its gentle rhythm relaxed him like a lullaby, leaving him with a deep sense of peace. After a while, though, Uaxac began to feel uneasy. All of his life he had been taught that the gods looked upon simple people such as himself with distaste. Only priests and their chosen followers were worthy enough to commune with the gods. A lowly fisherman such as himself surely had no place before the mighty T'unu-kan, and for him to bask in the blessings that by all rights were reserved for those holier than himself was an unthinkable presumption. What if the god were to awaken and discover that he had bestowed his blessing upon a common man? Sobered by the thought, Uaxac stepped back, fell to his knees, and bowed his head low. "Forgive me, Mighty One," he whispered earnestly. "I meant no disrespect. I shall leave you to sleep in peace, and will bring those more worthy of your favor to your presence tomorrow." There was no reply. The god slept on. Uaxac rose to his feet and bowed once more, then turned and begin to pick his way as silently as he could across the broken trees that T'unu-kan had knocked down to make his bed. He intended to find a sheltered place a respectful distance away from the god where he could build another fire and spend the night. In the morning he would return to the city and speak with the young acolytes at the temple. They did not impress him, but nonetheless they were learned in the ways of the gods, far more than he was. The boys would surely have realized by now that the death of their teachers had been the will of the gods, but rather a tragic accident. The ground quivered beneath Uaxac's feet. There was a low creaking, groaning sound, the same sort of noise that trees made when they bent before a storm. Some urgent instinct told Uaxac to duck; just as he did so, the stars vanished again and something heavy thudded down very close to him. He covered his head with his arms and cowered in fear, but there was no further sound, just the steady roar of the god's breathing behind him. Puzzled, Uaxac stood up... ...And immediately bumped his head on something that had not been there a second before. He reached up to see what it was, and found that something wide and warm and leathery was suspended above him. It was the god's hand. Uaxac's breath caught in his throat and choked off his terrified shout. He expected to be squashed flat at any moment, but minutes passed and the hand did not move. The god's breathing continued, slow and deep and steady. As time passed, Uaxac began realize that the god did not intend to kill him. Summoning his courage, he rose to his knees and reached up to explore the textures of the god's palm. It stretched over him like a great tent, its warmth radiating down upon him just as the sun's rays did during the daytime. Its colossal fingers curved down behind him, their tips buried in the soil. There was enough space that he could have crawled between them if he wanted to, but the meaning of the god's gesture was clear. Stay. Uaxac relaxed. His shivering ceased, and slowly he settled down on his back. A smile came to his lips as he reached up and rested a hand upon one of the god's fingers. "I understand, Great One," he whispered. "I am yours to command." With those words he fell into a contented sleep, warm and safe beneath the god's mighty hand. He awoke when the sun was already well on its way into the sky, and was surprised to find that the god's hand was no longer there. Blinking, Uaxac sat up and rubbed his eyes, then looked around. All around him the forest had been devastated, the trees lying flat, some broken, others torn up by the roots and thrown down. Dominating the tortured landscape was the enormous black form of T'unu-kan. He had rolled in his sleep and was lying now on his side, facing away from Uaxac. His back was wide and muscular, his shoulders truly immense, broader it seemed than the Sun Temple was high. Uaxac could see clearly for the first time the god's tail, a gigantic serpent of fur that could easily have surrounded a thousand men. Even in slumber its tip was restless, flicking into the air with a ruffling sound and then settling back to the ground every few seconds. Smiling, Uaxac stood and bowed to the gigantic creature. "Good morning, Great One," he whispered. T'unu-kan began to stir, a mountain come to life. Even though he knew that the god looked upon him with favor, Uaxac would not help backing away nervously as the huge body slowly rolled onto its back, the fallen trees creaking loudly as the giant's weight shifted upon them. The god's head remained turned away as he settled down again, his breathing returning to its low and steady rumble. When all was still, Uaxac cautiously moved closer. He knew in his heart that he had no business profaning the god's bed with his humble presence, but he could not resist the desire to us to see more of the magnificent deity, to explore every inch of his immensity. After all, had T'unu-kan not commanded him to remain through the night? Obviously he felt that this insignificant man had some use, or he would simply have swatted him like a mosquito. Uaxac decided that it would not be too great a sin to admire the god for a little while before returning to the city. T'unu-kan's sheer size, however, made it impossible for Uaxac to see more than a small part of him at one time. It frustrated him, and stepping back once more, Uaxac peered over the great black bulk of the god's torso until he located a tall tree that stood on the far side by the god's knee. If he could climb that tree to its top, he might at last be able to look upon T'unu-kan in his full glory. Uaxac began to pick his way around the god's body. It was easier for him to find his footing through the jumble of broken timbers now that it was daylight, but Uaxac took his time. It was not every day that a fisherman got the chance to see a god up close, and he did not want to waste the privilege. Slowly he wandered down the length of the god's powerful arm, stopping for a moment to study the great furry hand. The claws on the tips of the fingers were not as large as the ones on the toes that Uaxac had so unexpectedly encountered the night before, but they were just as smooth. He toyed with some of the ropy strands of fur for a while, fascinated by their warmth and texture, and then made his way past the god's hip. The muscles of the thigh were truly immense; the fur that covered them, rather than obscuring the details, followed every line and contour and accentuated it. There was a low gap beneath the knee that Uaxac could have crawled under, but he did not feel quite that bold. He continued along the length of the god's calf, past the ankle, and then around the edge of the titanic foot.

There he stopped for a while and stared in awe. The bottom of the god's foot was as black as the rest of him, and its shape showed just how perfectly the Sun God had melded the form of man and animal in his offspring. From the heel and upward for most of its length the huge foot was much the same as Uaxac's own, but higher up it was broader, padded, the clawed toes definitely not those of a man. It was the size, though, rather than the shape that fascinated Uaxac so. Mesmerized, he stepped forward until he could lay his hand upon the broad heel. Its warmth could be felt even at arms' length. He leaned closer, letting his body rest against the firm, leathery surface. In all of his life he had never seen anything so large, especially no living thing. The god's sole towered over him like a wall, tilted dizzily outward, its surface lightly pebbled and traced with lines and crevices that formed intricate and beautiful patterns. Ten men standing one atop another's shoulders would not be able to reach... Uaxac scrambled backward with a sharp cry and placed his hand over his mouth. The imagery brought with it the sickening awareness that it was this very foot that had stamped the hapless priests into the ground. He had seen their flesh clinging to it like squashed ants from below. His skin crawled and he swiped at his chest and arms, able to feel the presence of that dreadful gore upon him. The looming foot suddenly seemed ominous and terrible, an unstoppable force destined to pound him, his people, and the entire world to bits. "No!" He shouted the word aloud and covered his face. With a great effort he made himself calm down and tried to think clearly. T'unu-kan was not to be feared. The death of the priests had been an accident, nothing more. If he meant to destroy people, why would he have sheltered Uaxac so tenderly the night before? A wave of guilt surged through Uaxac's soul, so strong that it made him stagger. T'unu-kan could cause unspeakable destruction if he remained ignorant of the presence of Uaxac's people. He could kill thousands of them and never realize it. Uaxac alone had caught the god's attention, and yet he was selfishly wasting time gawking instead of helping his people to make their presence known. What to tell them, though? Uaxac himself was perplexed as to why the god had taken notice of him. How could he teach them what to do if he did not know what he had done himself? The sun was climbing higher in the sky. Soon T'unu-kan would awaken, and if he chose to return to the city, there was no telling how many people would be stepped on. "I will have to think of something on the way," Uaxac said to himself. Quickly he turned and climbed as fast as he could over the broken trees, and once he was out of the clearing he started to run. T'unu-kan knows me, he thought desperately. Maybe if I am in the city when he returns, then he will understand that they are my people. I shall tell them to do as I did, and present themselves to the god as his willing servants. It seemed like a logical plan, but it depended on his reaching the city before T'unu-kan did. He had seen just how fast the god could walk, and he lamented the time that he had squandered in satisfying his own selfish curiosity. He had no time to lose now, and he ran like he had never run before. The day stretched on, hour after weary hour. At long last Uaxac, hungry, sore and out of breath, reached the outskirts of the city and staggered toward the temple to tell the young priests what he had learned. A pair of very large men who were carrying spears stepped into his path and told him to stop. Uaxac tried to push past him, but they grabbed him by the hair and pulled him back. "Where do you think you are going?" one of them snarled. "Please," Uaxac begged, "I must speak to someone." "You again." That man was one of the ones that had dragged Uaxac away from the temple the day before. "You do not learn your lessons well." "I have learned a lesson!" Uaxac shouted. "I was with T'unu-kan all night. He held me safe beneath his hand. I must show you how to worship him or you are all lost!" One of the men slapped him hard across the face. "That is enough! We are not going to warn you again. Get out of here and do not come back. There is work to do, and no time to listen to crazy men babbling at us." Uaxac fell back, dazed. He raised his head to plead with them, and as he did so he spotted a column of men marching through the doors of the temple. Each one carried a spear over his shoulder. They walked in single file, their faces grim and determined. "What are they doing?" Uaxac asked with mounting alarm. "Why are they carrying spears?" The guards snorted at him. "T'unu-kan has been sent to destroy the weak," one of them muttered. "That is what the priests have determined. We must show him that we are strong and can fight him off. When he comes again, we shall be ready." Uaxac could not believe what he was hearing. "Priests?" he cried. "But the priests are dead!" "The old priests are. Their wisest students have risen to take their place." "But they are just boys!" Uaxac's voice was growing shrill. "Are they mad? You cannot fight T'unu- kan! He is as big as a mountain! He will squash you all like berries!" Another blow knocked him to the ground, and before he could get up a vicious kick sent him sprawling, clutching his ribs and moaning in pain. "The priests have more knowledge of the gods than you, Fisherman! Now go away. If we see you within the city again we will kill you." They brandished their spears to show that they were serious. Whimpering, Uaxac climbed to his feet and backed away, coughing. "At...at least let me have something to eat." One of the men laughed loudly, but the other thrust out his chin and said, "If we give you some food, will you go away and stop bothering us?" Uaxac hung his head. "Yes," he whispered. That man turned and disappeared into the darkness. Soon he returned with a sack and threw it at Uaxac. "There. Now get out of here, or else." Uaxac peeked into the bag. There were cakes and dried fruit and cornmeal inside. He was ravenously hungry, having had nothing to eat all day, and he gratefully tucked the bag under his arm. Without another word he turned and scurried away from the temple. He ate his food and then spent a miserable night on the ground atop the ridge from which he had watched T'unu-kan's march through the city. It was unbelievable to him that the people would have placed their trust in a pompous gang of boys, and even more unbelievable that they thought they could actually fight the god with spears. If they had stood by the giant's foot as he had, they would surely realize how futile their efforts would be. He was convinced that the only chance they had was to show the god that they were worthy of his notice. Poking him with tiny sticks might do it, but Uaxac doubted that the god would be pleased with them for it. "I will have to show him," Uaxac said as he fell asleep. "I will not move from this hilltop until T'unu- kan returns. When he sees me here, then he will realize that there are other people with me." T'unu-kan did not return the next day, though, nor the next, nor the next. Uaxac's determination to remain at his post faltered as his bag of food was emptied and hunger started to gnaw at his stomach. When nightfall came he crept down to the fields and stole some corn, and even managed to catch a chicken and run away before anyone saw him. During the daytime he stared at the horizon, watching for any sign of the god's giant silhouette. Below him the city's strongest men practiced with their spears. The boy-priests sometimes appeared, dressed in outlandish regalia that must have been meant to frighten T'unu- kan away. Uaxac shook his head sadly every time he saw them. He wanted more than anything to run down the hill and tell them that T'unu-kan would laugh at their costumes and that threatening the god with spears would only arouse his anger, but he was too afraid for his own life to venture forth. It was on the fifth day that the god appeared. Uaxac had been watching the activity in the city for a while and had then turned away to peer at the mountains behind him. When he turned back, T'unu-kan was there. His immense figure towered in the distance, framed between the big hills that formed the entrance to the valley. He began to walk forward, trees falling and dust rising around his feet with every step. Uaxac beat his head in sorrow and cursed himself. He had felt certain that the god would approach from the same direction he had left; it had never occurred to him that T'unu- kan might circle to approach the city from the other side. There was no way now that he could attempt to communicate with the god before he reached the city. Moaning in despair, Uaxac fell to his knees and uttered a silent plea that the young priests would come to their senses and welcome the god instead of trying to drive him away. The city had sprung into action. Rows of stout men with spears lined themselves up in the field that lay outside the city. Behind them, to Uaxac's dismay, hundreds of people began to crowd in. The priests, still clad in their outrageous costumes, were darting about the edges of the crowd and herding them forward. Uaxac guessed that it was all designed to be some empty-headed idea of a show of force. The ranks of the crowd swelled as more and more people poured from their homes and lined the streets. All eyes were on the approaching giant, whose footfalls were echoing now off of the surrounding hills. With each step he seemed to grow larger, and the people before him even smaller. The men with the spears steadied themselves and raised their weapons. Uaxac's body was painfully tense. He could barely breathe. His heart throbbed so hard in his chest that it was beginning to hurt. T'unu-kan pounded closer. One gigantic foot crashed down just in front of the row of spear bearers. The other foot came down beside it, and the giant stopped. Slowly he lowered his head, his deep brown eyes playing over the crowd. His brow knit curiously and he crouched down to peer more closely at them. Uaxac was astounded! He began to yell and dance about excitedly. "It worked!" he shouted. "Those stupid boys got his attention after all!" T'unu-kan had indeed noticed the people. He rested his forearms on his knees and stared downward, his head turning first to one side, then to the other. His nostrils flared. Behind him his enormous tail swayed pensively. Then, to Uaxac's horror, the god reached down and swept a massive hand through the ranks of the spear bearers, brushing them aside like dust. That same hand then swept forward and came down, fingers outstretched, in the midst of the crowd; the fingers closed, scooping up a writhing mass of people and lifting them high into the air. The great hand then turned over and opened, and for an anxious moment the god simply gazed down upon the tiny creatures huddling in his palm. A few fell from the edges and landed on the ground between the god's feet and lay motionless. Uaxac's knees buckled and he whimpered, "No, no," to himself as the god leaned his head back and lifted his captives over it. His mouth gaped open and his hand tilted upward, dropping them all inside. "Please, T'unu-kan," Uaxac whimpered, "Forgive them. They should not have defied you." The rest of the people panicked at the appalling spectacle and began to shove and claw at one another to get away. High above them, little arms and legs wiggled from between the god's lips. He licked them inside with a flash of his tongue and began to chew. Uaxac could hear their bones crunching even over the distant screams, and it sickened him. T'unu-kan licked his lips and then dropped his gaze again, his eyes gleaming hungrily. His hand came down on its side, forming a black wall that swept backward, herding a large group of people before of it before snatching them up. They too were borne helplessly into the air and dumped into that terrible maw, the mighty teeth crushing their screams into silence T'unu-kan swallowed and reached down for more. The people were racing about below him like frightened ants. Although they were running, their movements from the distance looked pitifully sluggish. The god caught them easily. He was not chewing much anymore, and Uaxac imagined that some of them were still alive when they were swallowed. As the crowd began to disperse, T'unu-kan leaned over them. First one hand, and then his knees landed with a shuddering boom upon the ground. His other arm stretched forward, his fingers reaching far into the center of the fleeing crowd and sweeping dozens of them back toward him. Their bodies piled up in a tangled, squirming heap that grew larger and larger as the god scooped more and more bodies into it. When at last he was content with the number he had gathered, the god bent and cupped both of his hands over the pile. The muscles in his arms bulged as his weight bore down. There was an awful crackle, like the sound a pine branch makes when thrown onto a fire. Juice squirted out from between the god's fingers, and the corners of his muzzle turned up in a satisfied smile. Licking his lips, he sat back on his heels and ate heartily Uaxac was numb. "This is my fault," he whispered over and over to himself as he sat on the ridge and watched the carnage. His cheeks were wet with tears. His ears rang with the sounds of terrified screams and of people being eaten alive. He cursed the priests and their self-important followers who had brought the people to such a dreadful fate. If only he had been more forceful with them. He could have made them listen, but he had been too timid. The guard at the temple had been right: T'unu-kan did punish the weak. Uaxac was being punished for his weakness in not bringing the god's message to his people, for not having the strength to lead them into the god's favor. How cruel of the gods to destroy an entire people simply to punish a single fisherman for his frailty! Unless... A profound understanding stirred Uaxac's soul. Jumping to his feet, he swept the tears from his eyes with his forearm and then charged down the hill toward the temple. T'unu-kan's murderous rampage, Uaxac now realized, was not a punishment but a lesson. It was obvious now: those who stood and waited for the god to come to them were beneath his notice; they were insects to be trampled and forgotten. Those who screamed and ran about in blind terror were nothing more than cattle, meat for the god's belly; but those who, like Uaxac, approached the god with love for him in their hearts and stood firm in his presence despite their fear -- they would enjoy the god's blessing, and would sleep safely beneath his gentle hand for all time. Uaxac now understood exactly what he needed to do to save his people. T'unu-kan had risen to his feet and had entered the city. He was stepping on houses, but with far more deliberation than during his first visit. Each time one of the wooden structures collapsed beneath his foot, he would scrape the wreckage away with his toes and then bend to pluck the dead and dying from the ruins. He cornered those who tried to flee through the streets and ate them, as well as the animals that were corralled in the marketplace. As Uaxac ran toward him, he bumped repeatedly into terror-stricken people rushing in the other direction. "No!" he shouted at them. "Do not run! Come with me and show the god that we are worthy!" No one listened, though. Their fear had made them deaf and blind. The god was no longer smashing the houses. Instead, he was crouching and pulling the roofs off one by one, tossing them aside and reaching within the walls to capture the occupants alive. The contented smile on his lips as he swallowed them made it plain that he preferred his meat alive. He soon discovered that if he simply stomped his foot hard in the street, some of the houses would collapse on their own and tiny people would pour out into the streets. They would not get far. Uaxac kept running, dodging fleeing refugees as he made his way through streets and alleyways, drawing ever closer to the towering god. At last he found himself on a wide, straight road that led directly to where T'unu-kan was standing, just in time to witness him slaying a group of men who were trying to flee past his foot. The god had spotted them while his hands were full of other victims, and apparently he had decided that they should die before he would let them escape. His foot rose and followed them in their frantic flight. They screamed and covered their heads as the shadows of his toes overtook them, and then they disappeared. One man, though, was faster than the others and managed to leap clear of the descending foot. With his eyes bulging with fright, he ran straight toward Uaxac while T'unu-kan finished off his victims and then turned his attention downward again. Uaxac recognized him as the guard who had given him the bag of food. The man was howling and sobbing as he ran. A shadow fell over him, and the god's gigantic fingers surrounded him. "T'unu-kan! Please, not this one!" Uaxac was surprised at the strength of his voice, and even mores when T'unu-kan heeded him. The huge fingers pinched the man's body tightly between them, and then abruptly let go, dropping the man several feet to the ground. The god turned his attention to something on the next street; as he bent down, the sounds of shrieking voices and lowing cattle rent the air. The man was trembling and gibbering as Uaxac approached him. "Stay away!" he blurted. "Be at peace," Uaxac said with a kind smile. "It is me. Don't you remember?" The other stared, and then he looked around wildly. "The...the monster...why did he...?" "He is not a monster. He is T'unu-kan, the Child of the Sun. He spared you this one time because I begged him to; he is not likely to do so again. Now, tell me your name." "N-Nukokul," the man stammered. "But..." Uaxac shook his head. "No questions. Nukokul, do you want to save our people?" "I...yes...but how?" T'unu-kan rose to his feet once more. He stood over the two men, a great looming shadow of muscle and fur, but he did not look down. With one mighty step he disappeared over the roof of the storehouse that the men were standing next to. His earth-shaking footfalls were accompanied by the crashing of wood in the distance. Uaxac grabbed Nukokul's arm and pulled. "Come on." "Where are we going?" "To follow him." Uaxac led the sputtering guard through the streets, craning his neck at every corner to try to keep the god in sight. T'unu-kan was moving slowly, studying the landscape beneath his feet as he walked. Everywhere they encountered wrecked buildings and deep footprints gouged into the streets, and every now and then the remains of someone who was not fast enough to get out of the god's way. As they rushed from block to block, Uaxac explained his revelation to Nukokul. "If there are two of us, the god will see that I am not the only one of our people who worships him." "I don't know if I can," Nukokul panted. "I know you can. He knows you can. You must have courage." "I wish I had a spear instead." Uaxac glowered over his shoulder and Nukokul was silent. They arrived, winded, at the courtyard of the temple just as T'unu-kan raised a mighty leg and stepped down almost precisely into the spot where the priests had been killed. Uaxac saw that as a sign and stopped short. "Wait here!" he said urgently. "Wait? Aren't we supposed to be following him?" Uaxac pointed. "Look." There was activity at the summit of the temple. A massive ziggurat that rose high above any other structure in the city, the temple had a flat, square crown large enough to hold a small army. The priests had always used it to greet the sun each Solstice. Now there was a small collection of garish figures leaping and cavorting about on top, their bodies gyrating wildly, their oversized costumes fluttering in the wind. "The priests!" Nukokul exclaimed. "Whatever are they doing?" "It does not matter," Uaxac said, shaking his head sadly. "They are about to die." Despite their frenzied efforts, T'unu-kan paid no heed to the priests. He stood before the temple in the center of the courtyard and stared up at the sky. Briefly he fingered the metal pendant that hung from his neck, then picked idly at his teeth with a clawed finger and flicked away some shreds of clothing. Then, without a single glance at the priests, T'unu- kan turned his back to them, flicked his tail skyward, and sat down on the temple's broad crown. The boys continued their frantic dance right up until the moment the god's rump settled upon them. "He has reclaimed the temple," Uaxac said solemnly. "Now it is up to us." The god rested his hands on his knees and peered at the sky. His dark eyes seemed wistful. Drawing a deep breath, he leaned back and let one hand slip between his legs. His fingers began to knead softly, and before long a black penis of indescribable size rose into view. The god's hand closed firmly around it and began to stroke along its length as swelled larger and grew rigid. Uaxac patted Nukokul's shoulder. "Come on." "What?" Nukokul was incredulous. "You can't be serious." "I am. Come along." Nukokul swallowed. "I do not think this is a good time to disturb him." "Remember what I told you," Uaxac said gently. "It is all right to be afraid. But you must come to him despite your fear." Still muttering nervously, Nukokul followed Uaxac into the courtyard. The god's gaze did not shift from the skies; his hand continued its slow, steady rhythm. Uaxac strode confidently across the sand, until he stood before T'unu-kan's mighty foot. Nukokul crept up behind him, shuddering and wheezing in fear. "I do not think this is a good idea," he croaked. "Hush," Uaxac whispered, smiling. He lowered himself to his knees before one gigantic toe and reached forward, laying his hands on the claw as he had done in the forest in the dark of night. "Do as I do."

Nukokul obeyed, although it took him a few moments to work up the courage to approach the mammoth foot. He sat himself down by another claw and cast worried glances back and forth at Uaxac, and up at the god's towering leg. T'unu-kan did not acknowledge their presence. His tongue had curled from his mouth and was now resting against his upper lip. His hand was moving faster upon his erection. "He does not know we are here!" Nukokul whispered urgently. "He knows." Uaxac closed his eyes. Calmly he leaned forward and let his cheek rest upon T'unu-kan's claw. The sound of the god's breathing was growing deeper, the low rumble mingling with the hiss of flesh upon flesh as he pleasured himself high overhead. Suddenly the god's toes curled, the claws digging into the ground. Nukokul let out a startled cry and leaped backward. "Run!" he shrieked. "He'll kill us both!" Before Uaxac could say anything, the terrified man turned and bolted across the courtyard. At that moment the god's pleasure gave voice to a bellow that shook the mountains in the distance and rattled Uaxac's bones. T'unu-kan's massive body shuddered; his fingers clenched tightly on the black bulk of his penis, which then erupted with the force of a raging river. A thick white stream burst skyward, climbing in a long, gossamer arc that caught the sun's rays and turned them into a brilliant rainbow. Well beyond the courtyard it fell to earth, striking the roof of a storehouse and caving it in with its weight. The god roared again, and Uaxac watched as another stream gushed forth, this one curling back upon itself in a bizarre aerial dance before landing with a loud splash in the distance. The third stream shot higher into the air than the first two, and as it curved back toward the earth it descended straight toward Nukokul's fleeing form. Uaxac grimaced as he watched the god's seed crash violently down upon Nukokul, battering him to the ground. The remainder of the stream buried him deep in its suffocating embrace. He twitched feebly for a few seconds, and then lay still. T'unu-kan's breath rushed out all at once and his immense body relaxed. His face was blissful, his eyelids drooping contentedly as he lowered his head and gazed straight down at the little man who was kneeling before his foot. Uaxac peered back, unmoving, unafraid. After a moment the god looked away, then stood and rose up onto his toes, his arms rising in a titanic stretch. Uaxac obediently stepped back as the god's foot rose and then swept rapidly over his head. It fell upon Nukokul's semen-covered body, and left behind only a sad red smear when it lifted again. T'unu-kan strode onward, leaving the city behind as he stepped over the hill and left the valley. From the other side of the ridge Uaxac could hear the sound of smashing trees as the god prepared his bed for the night. Only after those sounds had faded completely did Uaxac leave the courtyard to begin gathering the survivors. This story is copyrighted. Links may be made to it freely, but it is under no circumstances to be downloaded, reproduced, or distributed without the express permission of the author. Address all inquiries to rogue-dot-megawolf(at)gmail-dot-com |